The world of woodworking is as layered as it is intricate, and the differences of approach found between Japan and the West are both profound and remarkably fascinating. What it boils down to, if we are to distill the two styles, is a differing opinion of values in addition to worldviews that are incredibly distinct from one another. It is therefore not only a vast geographic expanse that divides the East from the West, but also their beliefs about wood.

To the Japanese, the approach to woodworking is philosophical, almost spiritual. The woodworker works in conjunction with the natural world. The method by which to abide is with nature, not against it. Wood is not seen as simply a material to be used but rather a material to be worked with, thus a partnership is formed. Furthermore, wood is considered a living organism, an organism which expands and contracts within the surrounding world we inhabit.

Therefore, wood is not cut down for utilitarian purposes alone, but instead is given a second life, is reborn in the form of a house, a piece of furniture, a sliding sho techniques that have been used for centuries and have been proven to pass the hardest test of them all, the test of time.

In order to fully grasp the art of Japanese woodworking one must first understand the techniques which they employ. Here are some of the most popular Japanese woodworking techniques:

Joinery (an overview)

‘Joinery’, literally the joining together of pieces of wood to form more complex wooden compositions, is the quintessential technique used by the Japanese. There are two main reasons for this. 1) Wood is plentiful in Japan. 2.) Wood withstands earthquakes better than brick or stone and proves to be the best alternative.

With Japan being a country prone to earthquakes, the benefits of joinery are obvious and numerous. Joints are designed specifically with flexibility in mind, that is to say, they give, and are able to withstand the sometimes massive jolts caused by quakes. This technique has been used in the construction of countless structures which have stood for centuries.

The goal of the technique is to be both strong as well as aesthetically appealing. Joinery does not require the use the use of nails, screws or bolts of any kind, making the finished product appear seamless and elegant.

Dovetail Joint

Popular in furniture designs, the dovetail joint is often considered one of the more elaborate joints in the Japanese woodworking world. Trapezoidal pins and tails fit seamlessly together to provide a firm interlocking system and provide a substitute for for screws and bolts.

Cabinet makers and carpenters are big proponents of this innovative design due to its clean look and its ability to resist being pulled apart easily (tensile strength).

It is particularly useful in the making of cabinets, drawers and the corners of furniture, as well as in timber framing. This is, quite simply, the strongest joint for wood you can get. That being said, it can be one of the more difficult joint techniques to pull off, typically requiring a higher level of workmanship and precision. If you want to see the most intricate dovetail designs, take a look at the Japanese Sunrise dovetail.

Mortise and Tenon Joint

Think jigsaw. The mortise, or hole, is filled with the tenon. The benefits of such a technique are first of all, aesthetic. No unsightly nails or bolts can be seen holding the wood together here either. Once again, the external appearance is seamless while the inner workings of such a system are complex and intricate. Being that it is also extremely strong and durable, this joint can often be seen used in cabinets, door frames, tables, and chairs.

The tool used to create these innovative joints is the Japanese mortise chisel, which tends to be shorter than the traditional English or Western bolstered mortise chisel. Furthermore, because many of the traditional tools the Japanese use are built by hand, they exhibit a resiliency and rigidity that puts many of today’s manufactured tools to shame.

Sampo-Zashi

Sampo-Zashi combines the dovetail and the mortise and tenon to make an extremely strong joint that relies on absolute precision. We’re talking down to the exact millimeter. This is no entry level wood joinery, and for that very reason this technique is typically used by master craftsmen to build large temples and houses. Such mastery displayed by the traditional Japanese woodworkers still serve today as a tribute to their thorough understanding of wood.

Japanese Inami Wood Carving

![By Daderot [CC0], from Wikimedia Commons](https://www.makefromwood.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/Japanese-Inlay-300x260.jpg)

Armed with only chisels and knives, master carvers display extreme dexterity that push woodworking skill to the limits. Walking the stone paved streets of Nanto city today, one can still see the many wood carving workshops lining both sides, proof that Inami still thrives to this day.

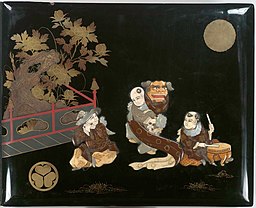

Japanese lacquering techniques

Once again, the Japanese have brought the art of woodworking technique to unmatched levels. In this case: lacquering. This finishing technique is what gives Japanese woodworking that magical luster and appearance.

More than just the spreading of a laquer over the finished product, Japanese lacquering techniques often have multiple steps involved including filtering raw lacquer and the use of a whetstone to perform any polishing duties necessary as a means to accentuate the beautiful grain, such as is seen in the Kujiro method technique. Moreover, by employing daring and innovative lacquering textures, the Japanese can even mimic the look of rusted metal, porcelain and even patinated bronze.

The process, as mentioned, is far from simple. Some lacquers require as many as thirty-three stages and can take many days finish. Patience, once again, is a virtue when it comes to Japanese technique. With nature, not against it. Nature, after all, takes time, and the results are often mesmerizing.